by Candace Palumbo

Candy and Tony

November 12th, 1983 was our small winter wedding reception in Toronto where my husband Tony and I first met. Following courses of Italian food and moving speeches we jived and danced for everything that night, to songs Tony mixed together from over five decades. He was an audiophile and I was just discovering the depth of his appreciation for all kinds of music. I still listen to those compilations often. We prepared our nondenominational service for that morning with our own vows and readings at St. Paul’s United Church but actually married officially at Toronto City Hall in July. I had already leaked our secret engagement to one of Tony’s six siblings, a sister of my vintage. Neither of us could hold it from his mom who gladly agreed to be our witness. We hushed that summer event until announcing it at the November wedding and did so to explain the greater meaning and brevity of our Church ceremony. It was light on some religious and official constituents and shorter than the proposal. Our personal vows, Corinthians, poets, Bach and the Beatles preserved 20 minutes. Together, we obliged many requests to recall that history out loud and it was fun to tell every time.

We enjoyed our occasions over dinner at home with family and friends, out for a pint, maybe to see a movie or play. Our anniversary fell on a Sunday in 2017 and I recalled fondly his parents’ family tradition of Sunday lunch… we would usually be there. We and our two children shared years of milestones, special days, sad days and ordinary ones with fresh home-made food and the animations of a large close family around this abundant table. There was always someone celebrating and someone to miss.

Tony died on July 24, 2014 at 59. He succumbed to mesothelioma, an incurable cancer caused by asbestos exposure. He had worked in construction for companies that no longer existed by the time he was diagnosed. He had also worked with his dad on different construction jobs; however, his dad’s memory was failing and I wasn’t part of Tony’s story until after he had finished studying at York University. It was difficult to obtain the information we needed to complete a claim with the Ontario WSIB, a challenge for many with mesothelioma because of its long latency – over 25 years. Companies fold or change names. There must be a link between the diagnosis and occupational asbestos exposure for a worker to be compensated. The Canada Revenue Agency expedited Tony’s request for his archived tax returns which verified the company names and the dates he worked. The WSIB accepted Tony’s claim and provided much-needed financial and medical support.

Confirming a mesothelioma diagnosis would take months. Tony’s shortness of breath in late June of 2013 could no longer be resolved with his inhaler, bike riding or vigorous gardening. The remarkable fatigue concerned me and I asked him to see our family doctor. He could see me fretting from inside…“It’s probably something simple, maybe just a different prescription…” He would tell me he was still strong and healthy and it would be fine. He was more concerned for me and our daughter. What was this now? He was active, ate well and had regular checkups. He read and challenged himself. We were all working and learning. A close circle of long-time friends and newer ones cared about us. We loved our kids and each other. We had a dog. These are things you need as a person, a partner and a parent to absorb and deflect coming losses.

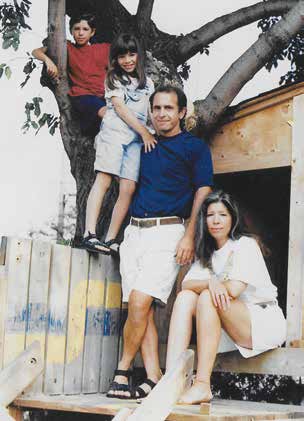

Candy and Tony with children Emma and Dylan

Family and friends joined us with our daughter Emma at home on the evening of July 12, 2013. It would have been the birthday of our son Dylan who died on April 25 that year. We had gathered again to honor the memory of his life. We were all grieving; still in slow motion and in the weeks ahead we would assemble one August evening for a special memorial tribute to Dylan that Emma and friends had organized. Tony was nervous that night, not feeling well, but he spoke to Dylan’s friends, listened to their stories about him, the music he made with them, the poems and spoken words and appreciated their art on the walls. The kids spilled onto the sidewalk, packing up instruments, mingling through hugs and tears and saying goodbye. We went home late; both of us worn and no one knew anything yet. We were waiting for a negative result on his chest x-ray.

No. The family doctor called him back in quick time to discuss the results. The night before Tony’s appointment we made dinner for close friends visiting from B.C. and he casually shared this news which they took in with obvious and quiet worry. This was the last time we would have any ease about Tony’s health condition. He waited for me to return home from work the next day to give me the news. There were four large masses on the right lung and he had a specialist’s consult pending. Emma was missing her brother terribly, studying at Ryerson and working. Tony was adamant that no one should know until there was something more definitive to report. I was between the power of denial and the brutal forces of anticipating this man’s suffering and his absence from my own life and so many others. I called Emma. I visited Tony’s sister’s house and his eldest sister was also there. Tony was bike riding with a friend when I texted him to join us. Getting off his bike in the driveway where I was waiting in tears, he gave me a hug and said “it’s ok, I told someone too”. That was a weekend in September.

The working diagnosis was adenocarcinoma but the specialist advised a biopsy to be sure. We both researched this condition, its symptoms and treatment. He was losing energy, losing weight and falling asleep too early as we watched our favorite shows after dinner. He was against risking biopsy because of the potential for disrupting cells and hastening the progression of the disease. Making this decision would become moot but not before we toiled over it, figuring the advantage of knowing the tumor type. Intractable focused headaches plagued him and defied relief in the next few weeks. Tony distracted himself with projects and ran his business reselling networking equipment from the home office. The market was slow and he worried about finances. His mind was turning all the time.

Word had spread and someone always came by to listen or hold us upright. Our messaging was full. We continued sharing communal dinners and spending evenings out or gathering for a backyard fire singing to someone’s guitar. Tony still loved meaty political discussions and stayed current with world news. The headaches finally overwhelmed his every move and our brother-in-law urged him to go to the emergency. It was a Friday in early October. He told me to go to work, saying I would be better off occupied with anything else. He called around 3:00 pm. I couldn’t breathe or think but I drove to meet him. He was booked for neurosurgery to remove a tumor from his cerebellum. Biopsy confirmed mesothelioma and that it had spread from his lung. We were told to get our house in order on October 16th and Tony should do things he enjoyed. Over the next few months, we met with a neurosurgeon, an oncologist, a radiologist, a thoracic surgeon, a social worker, four naturopaths and three palliative care physicians. Each of them described what they could do and left no uncertainty about the unalterable path ahead of him. Advanced pleural metastatic mesothelioma would end his life in two years or less.

Tony was discharged home where he wanted to be in November and would return to hospital as an outpatient. The day we came back through our front door together, I helped him to the living room sofa, knelt on the floor beside him and told him not to leave me. He said he wouldn’t, he would be here for a while. We still had to reduce the swelling around the incisions and address his visual and coordination challenges so he could function. Recovering from two lengthy brain operations was the least of the problems he would endure physically and emotionally. His thinking and sense of humor were changed and his body failing yet by the will and strength within him, he engaged and connected with all of us, telling us things he wanted us to know.

We never travelled to Italy and Scotland as we had hoped but Tony loved being with his family and enjoyed his home. Emma came up to spend time with her dad, cooking his favorite foods, running errands, talking about music and what seeds to plant. We walked our dog. We visited friends in Florida where he rode a bike and played tennis one last time with a friend he’d known since childhood. It was a welcome break from the sub-zero February cold in Toronto which he couldn’t tolerate any more. He was driven to finish projects around the house. We listened to music. He was ornery and stubborn sometimes and so was I. He worked in the garden again in spring and as always, I did what he told me to there. We attended funerals and birthday parties, played charades and had movie nights. We remembered camping trips, canoeing in Algonquin with the kids, hiking and horseback riding in the mountains out west and our trips out east. The morning before he died, he asked me to stop moving and sit with him and I could see that he couldn’t bear the weight of his illness.

We visit Tony’s memorial tree of life in in Toronto Cedarvale Park in the neighborhood where he grew up. In July, I take his ashes to the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia which I now call home. We had few separations in our years together by mutual choice. In his last ten months he needed my constant presence, my work and my care. I was mad when I got tired. I never imagined I would know the privilege of being all this for someone.

- A marathon of healing: Injured worker raising awareness and funds for invisible injuries - May 1, 2024

- Lighting a Candle this Day of Mourning - April 24, 2024

- Every dollar makes a difference - April 18, 2024

Find Support

Find Support Donate

Donate