by Stephanie Benay, CRSP

Recently, I went through a series of job interviews for a senior HSE position in Calgary. As it turns out, I didn’t land the role and was disappointed to hear that the organization felt I was “too passionate” about safety. Too passionate.

I thought long and hard about this. At first, I was distraught by the statement, and then I reconsidered. Let me share with you why.

His name was Bryan. He had a mop of curly brown hair, was wiry, quick to laugh and poke fun at anyone. He was from a large family, one of nine, and the second youngest boy. He grew up teasing his sisters and trying to keep up with his older brothers. His brother Butch described his as the “ladies’ man” of the group, with a twinkle in his blue eyes and a big grin. It was the 60’s when he was a teenager, and he grew up in a tough neighbourhood in Edmonton, quick to get into a fight and even quicker at charming the ladies.

Bryan and Stephanie

He had a love of aviation from his experience in air cadets as a youth so, at the age of 16, he joined the Canadian Air Force. He married young at the age of 20 to a woman he always said was the “most beautiful girl in the world” and went on to have two daughters. At the age of 21, he left the Air Force and got his dream job with Pacific Western Airlines (PWA).

With PWA he was a Load Master with the Hercules Operations (HercOps) team. Load Masters were responsible for the logistics of moving cargo. This group of aviation pioneers flew a total of six Hercules freighters into more than 108 countries around the world. They travelled more than 26 million miles and carried more than 800,000 tonnes of outsized cargo and bulk fuel shipments worldwide. They flew onto freshwater and sea ice runways in the artic and gravel, sand and unprepared runways in Africa. They worked in temperatures as low as -68°C in Northern Canada and +134°F (57°C) in the African deserts. They operated the aircraft around the globe and experienced life in strife-torn countries like Angola, Bangladesh, Chad, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan and Zaire as well as exotic locations like Amsterdam, Athens, Beijing, Cairo, Dubai, Hong Kong and more.

They moved cargo loads that included everything from cattle to nuclear reactor parts, helicopters to oil rigs, submarines to killer whales, relief supplies to wigs, monkeys and fish. The crews who flew these aircraft, maintained them, and managed them were the part of a unique brotherhood who shared tents on the arctic ice, enjoyed some of the best flying any group of aviators ever could and opened up the Arctic and the rest of the world. They were globalization pioneers.

However, it was the 1970’s and occupational safety, hazard assessment, and risk management were foreign to this fantastic group of men and women, to the companies who hired them and to Bryan, a young, adventurous innovator. Understanding the hazards associated with challenging environments, groundbreaking remote work, third world country parasites, insects and other factors weren’t even a consideration.

However, it was the 1970’s and occupational safety, hazard assessment, and risk management were foreign to this fantastic group of men and women, to the companies who hired them and to Bryan, a young, adventurous innovator. Understanding the hazards associated with challenging environments, groundbreaking remote work, third world country parasites, insects and other factors weren’t even a consideration.

While Bryan was working in Angola in 1979, he contracted a parasite that lead to an incredibly rare disease. It wasn’t a disease common to North America, and it took years to diagnose, and only after it had left him with bouts of blindness, paralyzation, and hospital-bound many times. This disease attacked his liver and hepatic system causing circulation problems that lead to repeated strokes, heart damage and legs that were black from breaking down and riddled with open ulcers. It was incurable.

But Bryan didn’t let any of that slow him down. For 40 years, he spent an hour every morning cleaning, medicating his wounds, bandaging and then wrapping his legs so he could go to walk, work and meet his commitments. He started every morning with a round of medications that were too numerous to count, just to keep his blood thin and circulating, his liver functioning and his heart pumping.

In spite of all this, he never complained. He never complained as he struggled into his “super suit,” a full body girdle that kept his blood from pooling in his belly, the countless blood tests, side effects and relentless pain. He had a job to do, grandchildren to play with and a golf game to win. He never held any anger toward the company, industry or business he stayed in his entire career. It was just simply, the way it was and there was a life to live.

Bryan’s daughters grew up, watching their father with wide eyes and understanding that their Dad had different struggles. He was brave and resilient, but they always were aware of his suffering and pain. His youngest daughter grew up to be a Family Support Worker and his oldest, a Safety Professional.

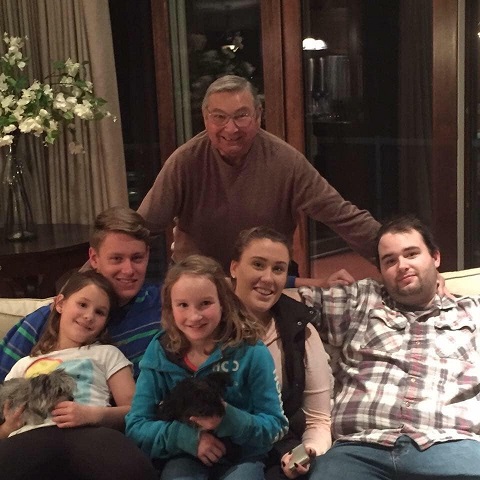

Bryan with his grandchildren.

On February 9, 2019, Bryan died in Edmonton, Alberta at the age of 72. He was surrounded by his daughters, sons-in-law and grandchildren. The constant pain was too much, his body was tired and couldn’t go on anymore. His liver failed and then his heart.

April 28th is the National Day of Mourning, a day recognized around the world to remember those who have lost their lives, or suffered an injury or illness on the job. In 2017, according to the Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada (AWCBC), this country recorded 951 workplace deaths. Each death brings a wave of despair to families, friends and colleagues. Not everyone dies suddenly in the workplace. Some suffer long, slow, painful deaths.

Bryan Benay was my Father, and yes, I am passionate about safety. I always will be. How could I not?

_________________

Stephanie Benay, CRSP is an innovative and accomplished Health and Safety Executive who helps companies seize the future through realizing the hidden value of HSE, Quality, Risk Management, Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility.

Stephanie Benay, CRSP is an innovative and accomplished Health and Safety Executive who helps companies seize the future through realizing the hidden value of HSE, Quality, Risk Management, Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility.

This post originally appeared on the Women in Occupational Health & Safety Society (WOHSS) blog, and has been reproduced with permission. www.wohss.com

- In Profile: Thunder Bay Steps for Life Committee - March 7, 2025

- Help us spread the Safety Message! - March 5, 2025

- Taking the first step for Steps for Life - February 6, 2025

Find Support

Find Support Donate

Donate