by Wildred Langmaid

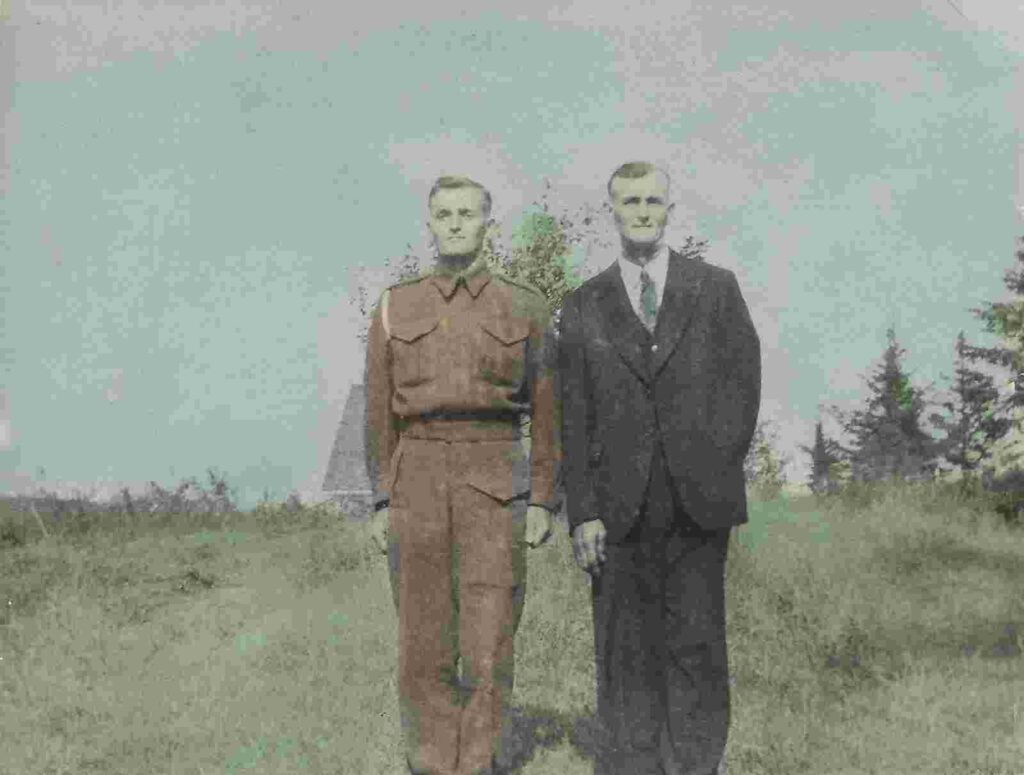

Leroy Maxwell with son Donald in 1941. Leroy died of silicosis in 1945, one year after Donald was killed in action in Holland.

I never personally knew my maternal grandfather, Leroy Maxwell, but his story was part of the narrative of my childhood. Born on Christmas Day in 1887 in Barre, Vermont, he died five days before Christmas in 1945 when my mother, his youngest child Sheila, was 14 years old. My grandmother, Della, lived with us throughout my childhood years. She and my mother talked about my grandfather’s hard-working ways, including how he would get up early every morning to go to work and then how he would spend his evenings after what seemed to me as a child to be a hilariously early supper. After supper, he would tend to a large garden of vegetables as well as some animals, ensuring in the process that there would be plenty of food for a family with six children throughout the year, even in the midst of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

While my grandmother took her children to church in town in the horse and wagon on Sunday morning, my grandfather was not in the habit of going to church after the young couple married in 1912. He would instead stay home and prepare a Sunday meal for his family – the one day during the week that my grandmother did not prepare the family meal. This change of pace forhim was his Sunday day of rest.

According to my mother, his specialty meal was “smothered steak”. From her description, it consisted of cuts of steak that would have been very tough if simply fried in a pan. However, he covered the steak with onions, made a gravy, and slow cooked it in the wood stove. In my mother’s words, “You could cut it with a fork.”

Only one of the Sunday meals was eventually not enjoyed. That was in a year during the depression when cash was scarcer than usual. The family remained well fed with home-grown vegetables placed in the root cellar after harvest like every year, but the meat was always either the deer or the moose that my grandfather and his oldest son, Donald, harvested while hunting that fall. Both my mother and my grandmother got so sick of venison that they never ate it again. However, all the family ate it without complaint that year, thankful that there was food on the table daily when many in the same area were struggling in the days when folks in need lived in “the poorhouse” and there was no form of social assistance.

My mother would often recount the one-liner that came if this man who personified the Protestant work ethic asked any of the children what they were doing, and they said, as children are wont to do, “nothing”.

“There’s plenty of that in the woodshed,” he would reply.

They were a happy, loving family managing in difficult times, but there was an unseen elephant in the room. The work that he went to every day was in a granite quarry. His family before him had worked in a granite quarry in Vermont, and he and his brothers came with their parents to St. George, New Brunswick at the turn of the 20th century to join a booming industry in an area rich in red granite. The extraction and processing of red granite replaced the lumber trade as the major industry of the area from the late 1890s into the 1930s. While many massive, elaborate gravestones were crafted and are found in local cemeteries, including dozens in the St. George Cemetery, and the town post office and the Presbyterian manse were constructed of the distinctive stone, many other pieces of work were crafted and exported. They included columns for the Parliament buildings in Ottawa, the base of an Ottawa war memorial commemorating the Boer War, stone for the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and columns for the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Boston.

My grandfather worked every day in the granite quarry. Living in the rural community of Canal, he would travel with others in that community by horse and wagon to the quarry in St. George – four kilometers there each morning, four kilometers back at the end of the work day.

A paper presented by Eulalia O’Halloran on July 4, 1968 to the Charlotte County Historical Society entitled The Granite Industry of St. George and Recollections of its People recounts the daily routine of workers like my grandfather:

“After the 7 a.m. whistle, the drills rattled; the granite cutters began their clinking; the surface cutters, column-cutters and polishers made their own heavy. steady sounds; the derricks squeaked as they moved huge stones from place to place — and mixed with all this clamour were the shouts of the workmen themselves.”

“The whistle blew again at noon, at one o’clock, and at four and, twice every day, crews of men covered with granite dust emerged from the mills. I used to meet them on my way home from school at noon.”

My grandfather was never the victim of a workplace accident, per se, but after years of working in conditions with no ventilation and no masks – one of those “men covered with granite dust (who) emerged from the mills” he suddenly became ill in his early 50s, and was eventually bedridden with what the local doctor dubbed stonecutter’s consumption. He was suffering from silicosis, a lung disease caused by breathing in silica from these tiny fragments over a period of time. Then, as now, there is no cure for silicosis. My grandfather died in 1945 at the age of 58, one year after his son Donald was killed in action in Holland during World War II.

Part of the story throughout my childhood was one of gratitude that such a horrible, preventable death did not happen anymore. Somehow, that was my view until this year.

At the Threads of Life Family Forum that I attended this year with my wife, Shelley, who lost her father as the result of a workplace accident in 2016, my viewpoint changed.

While many family members were at the Forum because they had lost loved ones due to an accident in their place of work, I also met some amazing people who had suffered lifealtering injuries while at work, and other heroes who were dealing with occupational diseases. I met families that included survivors of a specific type of workplace trauma; they were battling with lung disease caused by breathing in toxins from the workplace over many years.

I was thunderstruck, and simply ashamed of my sheer ignorance as a person who has been privileged to work at a desk or in front of a university classroom for the bulk of my professional career.

My first question: How is this still happening? Over 80 years have passed since my grandfather first showed signs of the toll the breathing in of toxins had on him while simply going to work every day to support his family.

My second question: What can I do? The answer to question two is to make folks aware that many people remain at risk in their workplace today. This reflection is a tiny effort in that direction.

- In Profile: Thunder Bay Steps for Life Committee - March 7, 2025

- Help us spread the Safety Message! - March 5, 2025

- Taking the first step for Steps for Life - February 6, 2025

Find Support

Find Support Donate

Donate