By Heather Maguire

The Last Time; March 2018, Belleville, ON

Dean pulled into the parking lot in his trusted Toyota Corolla, late. This was no surprise; Dean was never really all that good at being on time for stuff – except for work, that is. He was rarely late for work. I could see our daughter, Mae, just turned 12, sitting in the front seat. Dean had been upset that she was old enough to sit in the front seat; he didn’t think it was safe on the highway. “She is safer in the back, Heather, she is just safer,” he said. We had met in this parking lot every other Sunday for the past four years since we had separated, shuffling our youngest daughter between our two houses – his in St. Catharines, mine in Ottawa.

Dean pulled into the parking lot in his trusted Toyota Corolla, late. This was no surprise; Dean was never really all that good at being on time for stuff – except for work, that is. He was rarely late for work. I could see our daughter, Mae, just turned 12, sitting in the front seat. Dean had been upset that she was old enough to sit in the front seat; he didn’t think it was safe on the highway. “She is safer in the back, Heather, she is just safer,” he said. We had met in this parking lot every other Sunday for the past four years since we had separated, shuffling our youngest daughter between our two houses – his in St. Catharines, mine in Ottawa.

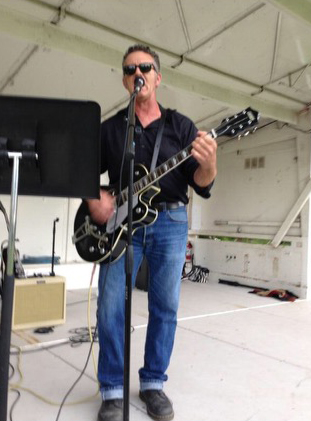

I can still see him standing there, wearing a new plaid shirt tucked into his jeans, his greying hair carefully styled – he was always careful with his hair. He looked healthy and happy, his eyes sparkling as he told me about his latest favourite music that he and Mae had been listening to on their drive. That’s the thing with Dean – you could always count on him to talk – about our kids, music, politics, and hockey. Go Leafs Go! We said goodbye, he gave Mae a big squeeze, and we headed off in our respective directions on the 401. Little did I know, that was the last time I would see him.

The Beginning; Winter 1988, St. Catharines, ON

Dean walked into the lecture hall wearing a hand-knit sweater with a motorcycle on the back – one that I later learned was knit by his mom before she died. He sat next to me, and we started to chat. We were in a first year Political Science class held every Monday night – he because he loved school and squeezed it in after work, me because I hated school and put off registering until the last minute, leaving night school as my only choice. Before long, we were talking regularly, and not long after that, he was baking me chocolate chip cookies and proposing.

Dean walked into the lecture hall wearing a hand-knit sweater with a motorcycle on the back – one that I later learned was knit by his mom before she died. He sat next to me, and we started to chat. We were in a first year Political Science class held every Monday night – he because he loved school and squeezed it in after work, me because I hated school and put off registering until the last minute, leaving night school as my only choice. Before long, we were talking regularly, and not long after that, he was baking me chocolate chip cookies and proposing.

He was 31 when we met, and I was 19. He worked for a sheet metal installation company, often working at heights. He loved his job because he loved being outside, he loved the fact that it never got boring with always being at a different jobsite, and he loved that there were always new and interesting people to talk to. He hated his job because, not long before I met him, he’d gotten his little brother, Tim, a job with his company for the summer, to help Tim pay his university tuition. Tim had fallen at work some 24 feet off a roof and was very seriously injured. Dean lived with that guilt, and he told me that he never forgave himself for not keeping his little brother safe.

The Safety Talk; April 2016, Lindsay, ON

Our eldest daughter, Connor, has just graduated from the Heavy Equipment Operator course in Lindsay and has landed a job at a local excavation company. She is excited and nervous. She calls to tell her dad; he is concerned that she has proper safety boots. She tells him about some of the places she is working; he tells her she should always be wearing a hard hat. She sends him a picture of her working a concrete saw; he asks about her safety glasses. This is the safety dance they do. She, excited for a new adventure; he, ever cautious that there are no shortcuts on her jobsite. He tells her that he is on the safety committee at work, and that nothing is more important than her safety. She believes him.

The News; March 27, 2018, late morning, Ottawa, ON

Connor is living in Orillia working at Shopper’s Drug Mart. We are on the phone as we often were, when she gets a phone call from a “No Caller ID” number. I tell her she had better answer the phone because you just never know. Two minutes later she calls me back. “It’s Dad,” she cries, “it’s Dad.” She tells me that the call had been from a policeman in Toronto, and that Dean had been hurt at work. I ask Connor for the name of the policeman and his phone number. I tell her to leave work, go to her apartment, and wait for me to call her.

Dean had worked in sheet metal since before I had met him – for more than thirty years – and he was always so safe. So when I spoke to the police, I actually asked if they were sure, because there was no way that the Dean I knew could have fallen. In a calm, steady voice, he told me that Dean had been working at Billy Bishop Airport in Toronto and had fallen off the roof. Although there were paramedics on site who attended to him immediately, he suffered catastrophic injuries and died at the scene. He said he was very sorry. He sent two police officers to my house.

The immediate aftermath of moments like that, contrary to what people say, are not a blur. Those moments exist in my memory in a permanent state of sharp relief, playing like a video in my head, keeping the details vivid. First, I called Connor back and talked her through what she should do, step by step, until I could get her. We lived four hours apart – a distance that never felt further. Then, I sat in complete silence on the couch and waited for the police. After they left, providing me with no new information at all, I emailed my work and cancelled my class. Stepping away from my desk, I slowly climbed the stairs, walked into the bathroom, and threw up. Then, more waiting, this time for Mae to get home from school.

There are many things that you plan for when you have two daughters – talks about love and puberty and schools and sports and friends – but this? This was something no mother can prepare for. As straightforwardly as I could – and as gently – I told Mae that her dad had died. Those words crushed her.

Court; January 2020, Toronto

Dean’s company, Vixman Construction, had been found guilty of failing to ensure measures and procedures of the Occupational Health and Safety Act were carried out. In other words, he didn’t have the proper safety equipment to carry out his job safely.

Try as I might, I could not reconcile this story with the Dean that I had known for so long. The man who lived with the guilt every day of his brother’s accident; who was constantly talking to our daughter about being safe on her jobsite; who couldn’t even manage to let our 12-year-old ride in the front seat of the car. How could such a safety-conscious person die like this?

Through these court proceedings, I learned that Dean had fallen 3.5 metres – only 11 feet – off a building at Billy Bishop Airport. They had been working at a higher level and had come down to this lower walkway to continue the work. He was wearing his self-retracting lifeline (SRL) and a full-body harness. However, there wasn’t the proper place for him to secure it, and so Dean let his line out about 6 metres from the anchor point and wrapped it around an upright column. As he moved about the roof, the block of his SRL somehow went over the side of the building, and because it wasn’t anchored properly to a horizontal anchor, it pulled him off the roof. He died instantly.

That day in court, my daughters and I read our Victim Impact Statements, asking the judge to make sure his death was not in vain. If the most safety-conscious person we know could die, just like that, then it could happen to anyone. The judge, kind as he was, stated in his decision that he was, “compelled to render a decision which deviates from the conventional deterrence and fine paradigm.” And so, in addition to a fine and probation, the company was ordered to make training videos and publish an article in a national safety magazine in Dean’s memory. This decision was overturned on appeal in 2022, leaving the fine intact, but not the health and safety materials. Our hope, through it all, is that nobody should ever die this way, and no family should ever have to go through what my family has endured. This was entirely preventable.

The Aftermath; Today

Little Wilson Dean, now two, runs around Connor’s house. He is a busy boy – one who loves excavators and tractors and pretty much anything with wheels. Connor reads him a book, ‘Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site’. He will never know his namesake, his grandfather. But we keep Dean’s memory alive. We tell stories, we talk about him, we make sure he is a part of all of our lives. When Dean died, I carefully sealed his T-shirts in Ziplock bags so that I could keep his smell on them for Mae (now 16), who still wraps herself in her dad’s t-shirts at night. I watched Connor’s life become unmoored; she was lost without her dad, and she has had to work so hard to rebuild her life. And our losses are endless. Anyone who knew Dean would say that he had an incredible memory, and it’s true. He had such a mind for detail, remembering things like particular plays in one of Connor’s hockey games from years ago, or a specific song that Mae was learning to play on the piano. He recalled such an incredible amount of detail about their lives, that it’s hard to even explain. When Dean died, so too did those infinite small moments of our lives, the funny stories, the big plays, the things that most people, me included, forget about.

On Grief

They say that grief comes in two parts. The first part is loss, and the second is remaking life. As we work to remake ours, each in our own way, it becomes more and more important to me that no other family goes through this. And so, I want to end with something that I hope you will remember.

Grief takes hold of us all, its tentacles long and relentless. I was devastated when Dean died and yet I didn’t know how to express that pain because we had separated. I didn’t feel like I had a right to be so broken, and yet here I was, shattered, trying my level best to hold tight to my daughters through their pain and yet not knowing how or where to place my own. My grief is complicated and messy, and it wasn’t until I attended the Threads of Life Family Forum that I found acceptance and compassion. Once you receive acceptance and compassion from others, you can begin to give it to yourself. So begins the healing.

- In Profile: Thunder Bay Steps for Life Committee - March 7, 2025

- Help us spread the Safety Message! - March 5, 2025

- Taking the first step for Steps for Life - February 6, 2025

Find Support

Find Support Donate

Donate