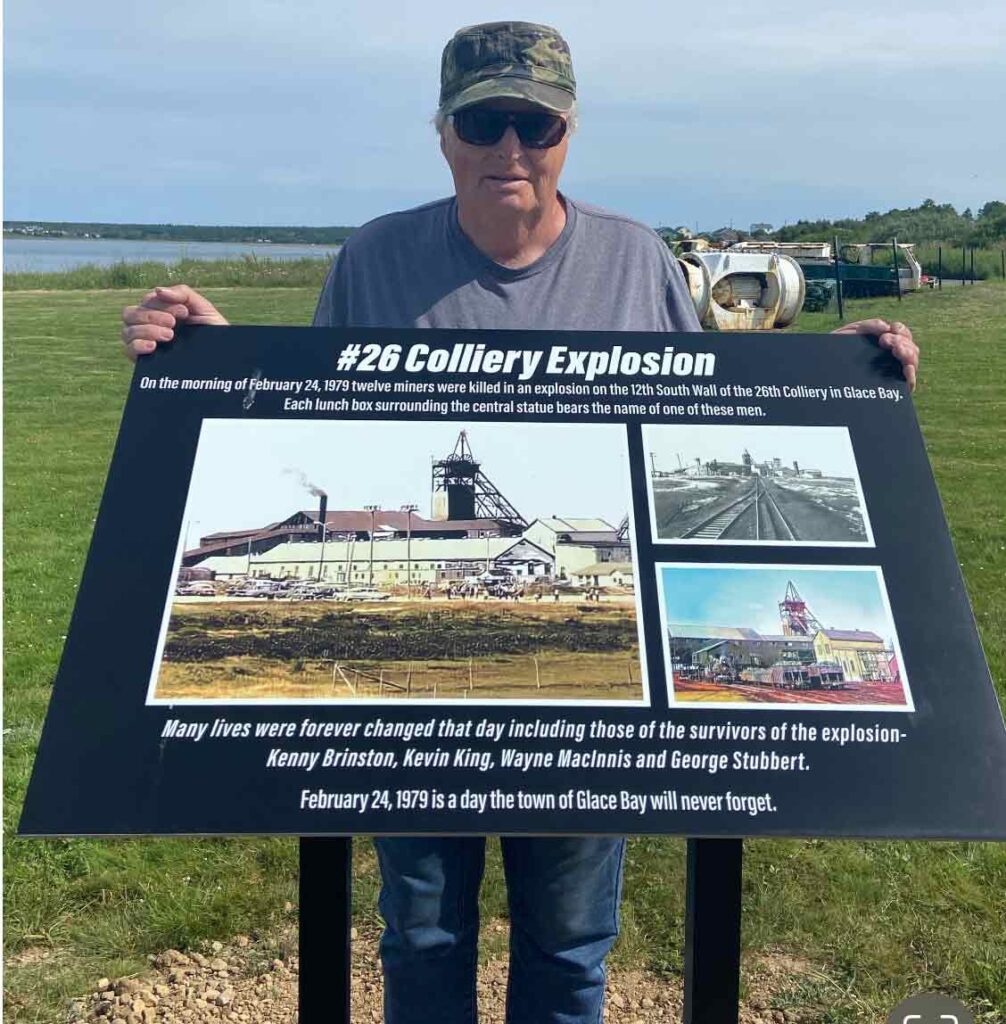

George at the site of the mine explosion memorial

The lifelong impacts of an explosion underground

On February 24, 1979, 16 miners entered No. 26 Colliery in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, to begin their shift. They were working the night shift from 11 pm to 7 am. They descended five and a half miles into the No. 12 South wall of the mine, almost 2500 feet below the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. The No. 26 Colliery was the biggest coal producer in the local area for many years and was owned by the Cape Breton Development Corporation, also known as DEVCO.

Around 4:10 a.m., a miner on the surface felt what seemed like the concussion of an explosion in the mine. He immediately notified mine management and by 4:50 a.m., the Draeger (or mine rescue) team arrived at the mine surface, followed by two doctors and a local priest. They entered the mine and were taken to the site of the explosion. The men working on the North wall knew something was wrong by the change in the air and were already on-site at the South wall. Despite the conditions where the explosion occurred, they immediately began the search. Men arriving for the dayshift were also recruited to go into the mine to bring the men out. Soon they found the 16 miners who were all located in the general area of the No. 12 South wall of the mine. Ten of the miners were killed almost immediately, succumbing to the effects of the explosion and noxious gases that filled the wall section after the blast. Six miners were found alive, although their injuries and burns were severe.

By 7:00 a.m., the six injured miners were on the mine surface and ready to be transported by ambulances to the local hospital. The plan was to stabilize the injured miners and then fly them by helicopter to Victoria General Hospital in Halifax to the burn unit. Freezing rain and fog, and winter weather warnings prevented any air travel so the miners were transported by ambulance, a five-hour drive, in treacherous road conditions. The rescue mission at the No. 26 Colliery was now a recovery effort. The bodies of the ten miners killed in the explosion were carefully gathered and taken to the mine surface. By 12:00 p.m. on Saturday, February 24, 1979, all of the bodies had been removed from the mine.

Four miners survived the explosion that day and returned to their families. Two have since passed away; two remain and one is my dad, George Stubbert. My dad worked in the coal mines since he was 17 years old. This was a job he loved. He was also a member of the Draeger team, the rescue team. He had competed in many Draeger team competitions with his fellow miners. He was trained to rescue in case of an underground accident or explosion and he was very proud of this.

On Feb 24, 1979, Dad left the house to work an overtime shift. This was the dedication of a young miner with a wife and three young daughters to support. I was 12 years old with two younger sisters, 11 and 4. He was 33 years old; “Handsome George” was his nickname in the pit, as he always showered after work and fixed his blonde hair just so, no going home with dirty pit clothes for this guy.

I remember the awful sound of the sirens howling on the morning of February 24. Everyone knew what they meant, there was a mine accident. They seemed to screech all day, such an eerie feeling and forever etched in my mind. Then the priest showed up at the door with a couple of other men. My mother, Hope, was inconsolable. I remember silently standing by her as she fell to the floor.

We were told very early on that his chance for survival was slim. Eighty percent of his body was third and fourth-degree burns, he was in shock, in a drug-induced coma and the burns were so severe he was unidentifiable from the other three miners. He had sustained an excessive amount of damage to his lungs from the fire and smoke of the explosion. When he did start to wake up, we were never allowed to visit him in the hospital, as this was his wish, always protecting “his girls”. There would be multiple reconstructive surgeries, skin grafts, and wound care to facilitate healing. Treatments were excruciating and for every tear he cried a nurse cried right alongside him – this he will always remember, and often speaks of. The medical team of the Victoria General Hospital, Burn Unit, in Halifax, NS became part of his family and his strength. Surgeries and treatments would continue for many years to come.

When he arrived home from the hospital months later, he was a stranger. He did not look like my dad. The scars on his face and his hands looked sore and the compression mask and gloves he had to wear were scary. The big apparatus on his hand and fingers looked similar to a torture contraption. His interactions were minimal and he was very reserved. I wanted to hug him, to talk to him but I was afraid. He was very thin. Before me appeared a shell of the man I knew as my father.

My youngest sister Holly was four years old. She did not discriminate; this was her Daddy. She ran to him and showered him with affection and love. She was too young to remember the before and after. She loved openly and freely with lots of hugs. She had lots of questions but the innocence of a child made them easy and safe for him to answer. This little girl was instrumental in initiating the emotional healing for our dad. I’m sure she is very unaware, even today, of the magnitude of the impact her love and innocence played in his healing.

It was difficult to watch my father struggle. He secluded himself, not wanting the public stares. People were so inconsiderate with their curiosity about someone who looks different. My dad was 33 years old when the explosion occurred. “Handsome George” now sees pain and sorrow when he looks in the mirror. He will forever remember all of the losses he has suffered. When he decided it was time to share his story, educate people, explain what happened, and address the stares, we knew he was on his way back to us. His fight continues daily, every day and night with nightmares and sleepless nights. Dad has since been diagnosed with PTSD but not until many years after the explosion. There was no help back in 1979 – when you were healed physically then you were healed. The injuries from this explosion were far deeper than the physical. As a family, we all suffered. Every day has challenges. We are all very aware when someone goes out that door they may not come back or life may never be the same. The fretfulness and anxiety never goes away.

Dad eventually did return to work for Devco. This looked different for him now he spent some time teaching at the University College of Cape Breton, training miners in safety. He enjoyed this very much and it reconnected him to society, to his peers. Following this, he made the decision to return to the coal mine to work on the surface in the monitor room. The comradery he always enjoyed with his fellow miners was so important in his transition back to the pit. He remained at Prince mine until he retired.

My dad’s greatest sadness has been my mother’s passing in 2010. For so long she had been his strength. She was there through it all with him and was until she passed away. He has often said when he was lying in the hospital after the explosion, he had the option to leave this world at any time. He chose to fight to stay alive for his family, his children, to raise and protect “his girls” and he always has. The pain and suffering he has endured is not lost on us.

He still keeps a pretty low profile in the community. It’s hard to be one of two surviving miners of such a tragic accident. This explosion rocked our little community to its core, no one will ever forget that day. In 2021 the Miner’s Museum erected a monument to the 12 miners who lost their lives in the 1979 explosion, lunch cans with each miner’s name engraved, and a plaque engraved with the names of the survivors. Miner’s Memorial Day 2022, a special service was held to remember these men at the museum, and the people of Glace Bay and surrounding towns showed up with standing room only. Dad did not attend even after multiple reminders; some things are hard to remember. I sat with many other townspeople and families and listened to “Big Jim MacLellan” recount the story of February 24, 1979. Jim was the mine manager on duty that fateful night. The town cried this day as they did the day of the explosion. He praised my dad for kicking into Draeger mode the day of the accident, stepping up and doing everything he was trained to do in rescue. He talked of how my dad remained calm and collected and knew what he had to do — unfortunately, the explosion was making its way down No. 12 South wall to where my father was located.

Dad continues to love, support and encourage us still today, and we are so proud to call him our Dad. This tragic workplace accident has shaped us into the adults we are today. I am a Registered Nurse, currently employed as the Manager of Clinical Services in a long-term care facility. My middle sister, Georgina is a Continuing Care Assistant with a background in Mental Health in Assistive Living and the baby Holly is a loving/mentoring teacher and guidance counsellor in Manitoba. We are the caregivers, the nurturers, both in our professions and with our families. Our successes in life have been the result of this strong, supportive, loving man we call “Dad”, who never gave up on himself or us.

The official report of the Commission of Inquiry into The Explosion in the No. 26 Colliery, Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, February 24, 1979, has determined the explosion was likely caused by “sparking produced by the action of the shearers’ steel pick … into a high ignition type of quarzitic sandstone. These sparks ignited a pocket of methane released from the coal during mining. The ensuing explosion was magnified when it ignited loose coal dust in the mine.” Despite the determination by the Commission of Inquiry that the explosion involved float coal dust and over the objection of the miners that ventilation was inadequate and rock dusting was not sufficiently applied to the mine surfaces, the company was not held liable. In fact, the Commission specifically noted that “Overall safety precautions were lax, allowing the explosion to occur, however, Devco was not solely responsible for this.” This determination made it possible for the company to successfully defend itself against accusations of any wrongdoing.

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) Secretary-Treasurer Levi Allen stated, “The explosion at the No. 26 Colliery was a tragedy, the likes of which Glace Bay had not experienced in over 70 years.” He said “It was, like mine disasters before it, an event that could have been prevented. Proper ventilation and adequate rock dust would have eliminated the ignition sources that permitted this explosion to occur, but like almost every other mine disaster we have seen, management’s first priority was production over safety. Then to have an official government body acknowledge these problems while absolving the company of responsibility, only added to the grief and pain of those left behind. The fact that 40 years have passed does not lessen that heartache.”

- Forty years does not lessen the heartache - August 25, 2022

- My hero, my Dad - June 13, 2019

Find Support

Find Support Donate

Donate